The Wheels of History

Seward's Carriage

For many 19th-century Auburnians and Washingtonians alike, the sight of the Seward family carriage passing them on the street was as welcome as it was familiar. The act of riding was highly social and conspicuous for the family, whether in their Central New York home or while in residence at the nation's capital. William Seward loved to be seen from his coach and, in nice weather, enjoyed partaking in a leisurely ride for its own sake, often with no destination. As he wrote about this habit in his memoirs: "When any time remained before the dinner hour... Seward would take his carriage, and drive with some of his family or friends." He recalled the delight with which he ordered his driver pull the reins so he could "stop to chat" with any interesting parties that he might encounter. "Occassionally," Seward recounted, "he would vary his afternoon drive by getting out of the carriage and climbing a hill, or strolling through a bit of wood."

It was little wonder, then, that Seward's Wood Brother's Company carriage—manufactured in New York City ca. 1850—was a source of particular pride. A stylish car referred to as a "barouche social," it featured two rows of facing leather-upholstered seats, a detached seat for the coachman, intricate metal work, and a retractable top. Eventually, the Sewards affixed their family crest to the vehicle's door. The carriage closely resembled the one later acquired by President Lincoln when he won the White House, though the Seward family (quietly) believed theirs to be the finer model.

As they became friends, Lincoln adopted his Secretary of State's fondness for excursionary drives, and Seward often invited the President to ride with him in his own carriage. They might escape the heat of the city for the Soldier's Home outside of Washington; on other occassions they rode out to visit with soldiers at encampments on the outskirts of the capital.

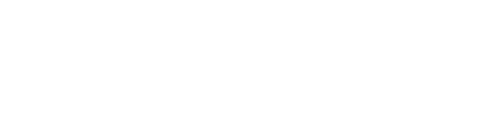

Fatefully, Seward was riding in his carriage on April 5, 1865, when he suffered a terrible accident that resulted in severe injuries to his upper body, including a broken arm, collarbone, jaw, and likely a concussion. Many of the doctors who treated him considered his wounds life-threatening. Ironically, it was because of this near-fatal experience that Secretary of State Seward almost certainly survived the attempt on his life on April 14th—the same night John Wilkes Booth assassinated Lincoln at Ford's Theatre. When co-conspirator and would-be assassin Lewis Powell entered Seward's Lafayette Square home intending to commit murder, he found the Secretary both well-attended (by family and military) and heavily bandaged. Although Powell managed to stab Seward multiple times in his recovery bed, he failed to land the mortal blow.

Seward survived both the accident and assassination attempt. Thereafter the carriage maintained a special place in the family's keeping. It returned to Auburn with Seward in his retirement, and was subsequently passed down to his children. When the Seward home became the Seward House Museum, the carriage was placed on display for generations of visitors to enjoy.

Woodshed, ca. 1880-1890

Deterioration set in over time, however, until the carriage fell into serious disrepair. Fortunately an immense conservation effort is underway. The firm B.R. Howard & Associates of Carlisle, Pennsylvania—the premier company that previously restored the carriages of Lincoln and George Washington—is currently at work. Stay tuned as the Seward family carriage makes its glorious return journey to Auburn, and the renovated carriage house building, later this year!

Designs on History: Two Fixtures from the Past Face a Bright Future

For just about 165 years, this elegant pair of stone structures have graced the back of the property on 33 South Street in Auburn. Although technically separate buildings, the Seward family's Barn and Carriage House are linked together as a set—architecturally in style, in the minds of generations of their neighbors, and through a shared history. Now, after decades of gradual disuse, the Seward House Museum is pleased to reopen both following a lengthy rehabilitation and preservation project.

The Barn and Carriage House in place today are replacements for originals that once stood near the same location along William Street. Sadly, those predecessor buildings were lost in an act of political violence perpetrated against the Seward family on April 17, 1860. At the time, Senator William Seward had emerged as the frontrunner candidate for his Republican Party's nomination for the presidency. Far from home with an election campaign underway, Seward was targeted by a local arsonist looking to send a deadly message. As dusk fell on that quiet mid-April evening, an unknown assailant crept onto the property and set ablaze an older wooden barn, carriage house, and some surrounding sheds. The arsonist seemingly hoped to bring the entire homestead burning to the ground as well. According to the Seward family's youngest son, William Junior (then 21 years old), who bore witness to the fire:

Before I could reach the barn, it was entirely enveloped in flames, so much so that is was impossible to enter. The middle shed and Carriage House were not then on fire but in consequence of the high wind and scarcity of water these buildings could not be saved. The house for a time was in...danger but by a well directed application of water there was no damage done.

Will Jr, 1864

Frances Seward was even more alarmed than her son by the close call. Surveying the wreckage herself, a few days after the fire, she reported how "...it was marvelous that the house was saved. The fences were torn down and the roofs deluged with water. The garden is covered with burnt shingles."

While the main Seward home was spared, the rest of the loss was devastating, including the deaths of the family's stabled horses. Resolute in their determination not to be cowed, the Sewards persevered. From the ashes of their ruined grounds, they rebuilt anew—a larger and stronger barn and carriage duo. For the family, they became a visual reflection that they would not be silenced. The thick stone walls that rose into place symbolized their intention to endure against any future threats.

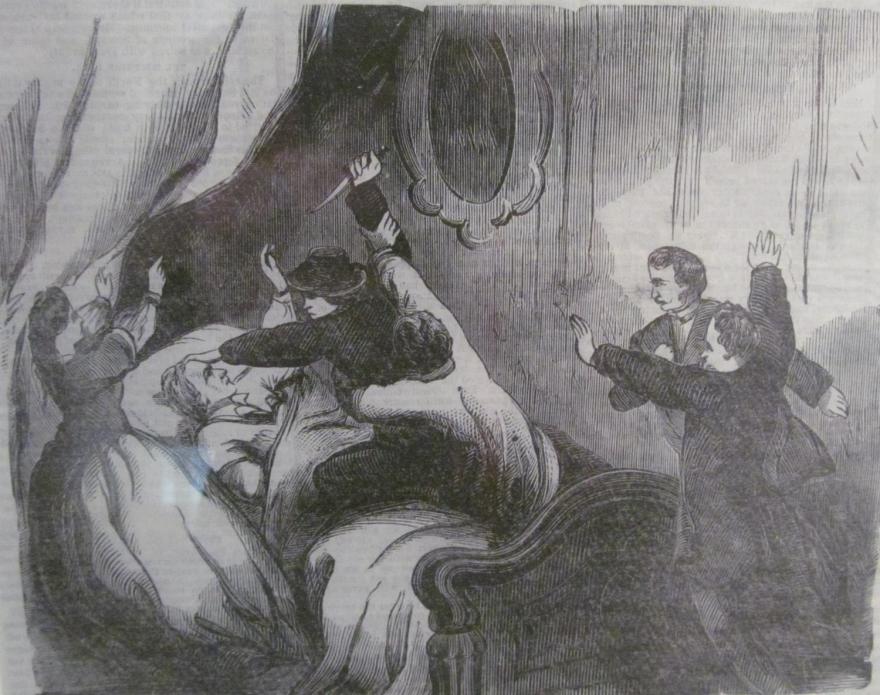

William and Frances' second-born son, Frederick Seward, personally completed the plans. Always a bit of an amateur architect, he drafted blueprints for buildings "that would be private and fireproof." Construction began quickly on Frederick's vision. The Barn and Carriage House were built from local limestone in an Italianate design that anticipated future additions to the house, particularly the South Porch, Drawing Room, and expanded Dining Room renovation of 1866.

Both structures featured symmetrical fenestration for its windows and doors, slate pyramidal roofs, and built-in gutters and cornices. Frederick himself insisted on conceiving of the project in terms of two close-but-unconnected structures that faced each other. "The separation, I think, is conducive to neatness," he wrote in early summer 1860. "The road to the William Street gate runs between. The doors of both buildings open on it, thus making each ease of access from the other, and keeping the interior of both out of sight from the house or the street." A cobblestone driveway with street-facing gate futher drew the two together.

The Barn, or lefthand-facing building as one approached from the house, combined striking form and utilitarian function. Its purpose was to contain stalls for horses and cows on the ground level, with space set aside for tack and feed rooms; above, a vaulted hayloft with a door that opened to the cobblestone below. As its name implies, the Carriage House afforded generous space on its main level for parking the family's carriage. It also featured living space upstairs, eventually used to accomodate residential servants for the family.

Stable and Carriage House, ca. 1870

Although the core uses for each building remained intact for decades after Frederick's work was finished, the family began making small changes. In 1870, for example, William Jr. began altering their intentions to "make more room," particularly, he noted, for the "fat ponies" he purchased for his young children.

Changes in technology wrought other changes to the pair of buildings. Just as working livestock slowly began to be replaced by pleasurable pets like portly ponies, so too did the gradual arrival of cars displace the need to store old-fashioned carriages. In 1923, the same year the house was fitted for electric wires and fixtures, the Carriage House was converted into a garage for an automobile. The upper level apartment received upgrades of its own, namely a plumbed tub, toilet, and sink.

Upon his death in 1951, William Henry Seward III (once the proud rider of one of those ponies) left the family home and property in trust to become the Seward House Museum. This bequest included the barn and carriage house. Over the next 70-plus years, the buildings had several uses. The apartment above the Carriage House, for instance, was retained by a family who had served the Sewards and who initially acted as live-in caretakers for the Museum.

Carriage apartment porch, 20th century

But mostly the Barn and Carriage House became storage facilities. Time took its toll and they fell into a state of disrepair. Yet they remained rooted in place, retaining their graceful 19th-century appearances even as the modern world shifted all around them. Today they combine both features: all of their original historical charm, newly adapted for reuse and ready to serve the visiting public for generations to come.